November 2013

Features

- 21st Century Revolution

Global comparisons reveal just how radically the demands of education are changing, says Andreas Schleicher, and how the UK and other systems need to respond or be left behind. More - Digital dangers

Students with special needs are among the most a at risk online but it’s also the area where guidance and examples of good practice are in short supply. Julie Nightingale highlights some of the good practice around for students with special needs and other ‘vulnerable’ groups while they are online. More - Don't panic!

A death or accident can knock an institution sideways but a good disaster plan will enable you to control the immediate fallout and also avoid lasting damage to students, staff and/or reputation, says Richard Bird. More - Closing the gap

From lifts to school to personal mentors and subsidised music lessons, Dorothy Lepkowska looks at the different approaches that schools are taking to maximise the effect of the Pupil Premium. More - Take your partners

If you’re not already a sixth-form collaborator then maybe it’s time to start, says Stephan Jungnitz. More

If you’re not already a sixth-form collaborator then maybe it’s time to start, says Stephan Jungnitz.

Take your partners

In 2010–11, budgets for post-16 education took a nosedive when the withdrawal of funding for ‘entitlement activities’ reduced student funding by about one-eighth.

The National Audit Office (NAO) recognised the challenge. In its 2011 report, Getting Value for Money from the Education of 16- to 18-year-olds, the first recommendation was that the Department for Education (DfE) “should disseminate information on how providers can collaborate through federations or other cost-effective means to improve choice of courses to learners, while achieving economies of scale”.

It didn’t happen and collaboration generally doesn’t seem to have been foremost in politicians’ minds. Funding for local 14–19 partnerships was removed and more competition was introduced into the system in the shape of university technical colleges (UTCs), studio schools, 16-19 free schools and new sixth-forms, all now proliferating.

Furthermore, the recent government announcement on creating up to 40 new career colleges that cater for vocational learning will cause additional tension and competition for post-16 providers unless there are some serious incentives for collaborative and partnership planning.

In 2013–14 the economics of post-16 provision is becoming even tougher with more cuts in 16-18 funding. A break-even class size is about 19 students and a reasonable range of AS and A levels needs a sixth-form of about 200 students. If student numbers are any smaller then a subsidy – perhaps a sizeable one – has to be taken from other activities.

Value added

Improving quality can be a driver for collaboration. Data for 2012 published on the DfE website shows that for small institutions with between 20 to 100 AS entries, the majority had negative value added and only 6 per cent had positive valued added. For larger institutions with more than 800 AS entries, nearly two-thirds had positive value added and 19 per cent had negative value added. (The numbers don’t add up to 100 per cent because there are some institutions where value-added is not statistically significant.) A level value-added data paints a similar, but less dramatic, picture, probably because students drop weaker subjects.

Attainment data for A levels for 2012 tells a similar story of small groups underachieving compared to larger ones. The median average number of students taking A levels, where less than 50 per cent achieved the minimum standard, is 27 students. Where more than 80 per cent achieve the minimum standard, the median number is 115 students.

There are exceptions to the rule – sometimes particular local factors are at work, and statistics generalise – but AS/A level student achievement is usually better in bigger cohorts, possibly because staff can become more specialised in AS/A level teaching with more students. The interaction between students in a larger group may also be more productive.

There is no data about enrichment activities, but whether it’s debating societies, Oxbridge preparation, a wide range of sports, performing arts or interests groups, it’s going to be easier to put on a good choice of high-quality activities if student numbers are high.

The positive affect that collaboration can have is not a new story. In 2000, HMCI’s annual report noted that “larger sixth-forms tend to achieve greater progress” and that “effective collaborative links with other schools and colleges… have resulted in students making good progress and achieving high standards”. At that time sixth-form provision was funded by about one-third more than Key Stage 4. Now it’s funded by about 20 per cent less.

Declining numbers

All the change in the pipeline may make collaboration more attractive. The number of post-16 students is, unhelpfully, in decline while new qualifications with greater rigour are going to be challenging to implement and future changes in accountability will mean increased scrutiny of how institutions are performing.

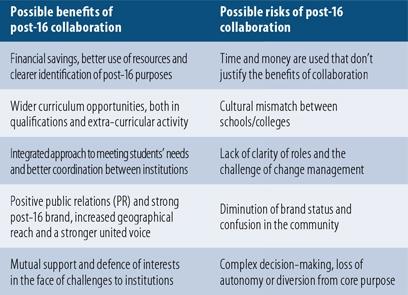

Addressing future challenges and young people’s needs may be better done through collaboration, although there are risks in collaborating, too. In the mid-1980s, for example, there were many school and college consortia funded through TVEI (the Technical and Vocational Initiative) but when the additional funding ended so did most of the consortia. They just weren’t economically sustainable.

In the past some local authorities (LAs) reorganised provision to create new sixth-form colleges, which have often been very successful. However, with the diminished powers of LAs now any such reorganisation is made almost impossible. It’s up to schools and colleges to work together to develop strategies and implement solutions.

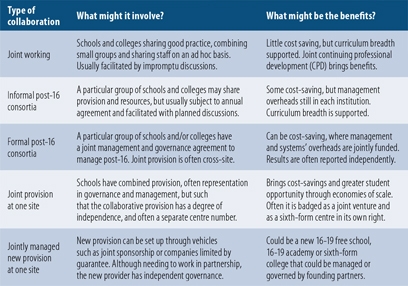

Up and down the country there are many examples of different types of collaboration, developed to meet local needs and circumstances.

Working for the greater good

Collaboration and solutions created by professionals working together don’t usually grab the headlines. A current media preoccupation is with individual and heroic leadership, and winning or losing in the local league table race. It’s a philosophy portrayed as one that will help the nation to international league table victory.

But it could hardly be further from the truth. Good leadership is surely about working in partnership for the greater good, rather than for institutional success with little regard for what happens elsewhere. So perhaps the question should not be whether to collaborate, but to what extent do we collaborate.

In a March 2013 survey on local accountability and autonomy in colleges, Ofsted stated: “Planning for new sixth-forms has not always been sufficiently well aligned to demand and demographics in the local area.” Schools and colleges working together for the benefit of an area seems to be called for by Ofsted, too.

And if you thought collaboration was only an issue in education then you’re wrong. The weekly newspaper Farmers Guardian reported from the annual cereals conference that “three-quarters of combinable crops’ growers are spending around £100/ hectare more on machinery and labour costs than they need to. But by collaborating, not only can costs be reduced, technical performance can be increased significantly.”

Collaborative approaches may not only be a method of succeeding with the future challenges for post-16 education but they may also help to improve cereal harvesting.

- Stephan Jungnitz is ASCL's colleges specialist.

LEADING READING

- Reception Baseline Assessment: Changes for 2025

Issue 134 - 2025 Summer Term - Embracing AI

Issue 134 - 2025 Summer Term - Improving attendance

Issue 134 - 2025 Summer Term - Anti-social media?

Issue 134 - 2025 Summer Term - Investment. Investment. Investment.

Issue 134 - 2025 Summer Term

© 2025 Association of School and College Leaders | Valid XHTML | Contact us